The So-Called Utopia of “2 B R 0 2 B”

By Daniel Coxson

“2 B R 0 2 B,” Kurt Vonnegut’s 1962 science fiction short story, imagines a future where old age and disease have both been solved. There are no prisons, wars, poverty, or any of the other ails of humanity, including unintentional death. However, due to subsequent problems of overpopulation, a system has been established to maintain a constant number of humans on Earth. The discussion of whether this is more of a utopian or dystopian society is told through three primary characters.

Edward Wehling is waiting in the Chicago Lying-in Hospital waiting room for his wife to give birth to triplets. Nearby is a painter who is close to finishing a mural called the ‘Happy Garden of Life.’ The mural is of a perfectly arranged garden where humans roam, each human representing a different worker at the hospital or of the Chicago Office of the Federal Bureau of Termination, the bureau responsible for peacefully killing anyone who willingly decides to die. The mural is meant to represent the “utopia” that has been created.

Dr. Hitz, the founder of the termination system, soon enters and announces that the triplets have just been born. According to the law, the triplets have to be killed unless the Wehlings can find three people to volunteer to die, since the population size always has to stay constant. Edward Wehling has only found one volunteer, his grandfather, who he’ll have to bring to the Bureau and then decide which of his three children to save.

At Wehling’s expression of frustration, Hitz responds, “You don't believe in population control, Mr. Wehling?... Without population control, human beings would now be packed on this surface of this old planet like drupelets on a blackberry!” At this, Wehling shoots Hitz, a woman in the room, and himself in order to save himself the pain of sacrificing his children and grandfather.

The painter, now left alone, considers that this might be the best possible world to live in after all, since it still doesn’t contain plague, war, or starvation. He calls the number of the Bureau. The painter is greeted by the “warm voice of a hostess” and sets up an appointment for that afternoon.

“You don’t believe in population control, Mr. Wehling?... Without population control, human beings would now be packed on this surface of this old planet like drupelets on a blackberry!” ”

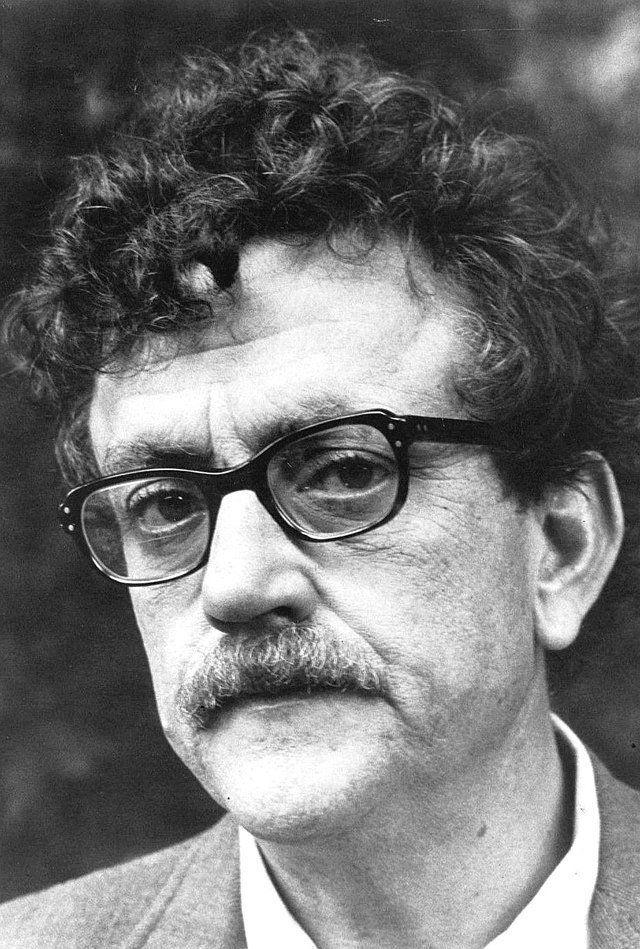

Kurt Vonnegut (1922-2007)

Still, the question is unanswered: is this so-called “Happy Garden of Life” a utopia? One argument is that of Utilitarianism, which might side with the painter’s final thoughts that, though imperfect, the Garden is the best of all possible worlds. Wehling evidently wasn’t satisfied with the system, but the millions of people that get to live disease and poverty-free, for as long as they want, appear to experience a pleasure that vastly outweighs the pain Wehling and any like-minded individuals feel. According to Utilitarianism, this might be the ideal system since it appears to maximize pleasure and reduce pain for the greatest number of people.

However, it is questionable whether a world without disease, poverty, and death is actually a more pleasurable world to live in. The painter, even when admitting that this might be the best possible system, is compelled to leave it. Wehling’s children would have to live knowing that they only survived because of homicide, a guilt that would likely weigh on them for their entire lives. It becomes questionable whether a system that creates these consequences is actually praiseworthy.

Further, the system is more specifically flawed in its disregard of family relationships. Wehling is forced to sacrifice three family members simply because he happened to have triplets, which evidently puts a great strain on him and, out of context, clearly seems to be a morally repugnant thing to do. Does the overall pleasure of the general population really outweigh the responsibility Wehling has to his family? One might argue that one’s responsibility to their family outweighs their responsibility to others, simply because it is a virtue.

Deontology would take another stance on this situation. Immanuel Kant argues that both murder and suicide are morally wrong. We could not rationally make either a universalized moral law, since there’d be no people left, and since murder uses people as means instead of ends. Wehling’s murder-suicide cannot morally be universalized, so therefore he is doing something wrong. But the termination system is also immoral. To promote the Bureau is to promote the destruction of human beings, which does not treat them as rational beings worthy of life but rather means of achieving a more stable population and planet.

However, this theory seems to catch humanity in a double bind. If we could permanently cure disease, poverty, and all the other problems of humanity, it seems like something that would be morally universalizable—after all, we would want all people to live without disease and poverty. However, this amplifies the problem of overpopulation, which would destroy Earth, and humanity along with it. It is simply a larger, more-drawn out method of killing humans, which Kant has already established as immoral. Whether you kill some people directly or all people indirectly, it’s immoral, but to destroy an entire planet and potentially all life in the universe seems to disobey the Categorical Imperative much more than the Bureau of Termination’s system. By choosing a system that does not allow murder or suicide, supposedly justified by the idea that you are treating people as ends instead of means, you cause both humanity and the planet to be destroyed.

From these theories, it appears that the Garden is far from perfect in any sense. It might generally be devoid of war, starvation, and unwanted death, but that does not make it a utopia. It has gotten rid of almost every problem humans could possibly have, so a Utilitarian might say it is the best option. However, it is obvious that a system where families are ripped apart and people are still murdered is morally wrong, and thus far from a utopian system.

One might argue that this system is morally broken because it undermines the virtue of upholding family relationships. Parents cannot give preference to their children, and family members can be killed for the greater good without our permission, clearly ignoring the strong connections we feel with our family members. However, the question should be asked whether familial love is more important than saving the planet. Wehling might have had to give up his children and grandfather, but he would have had his wife, and his cooperation would have helped all other organisms on Earth live securely. If anyone’s actions could be excused by a need to protect their family, no one would be willing to make sacrifices for the rest of humanity and we would all end up dying anyway. The Garden’s lack of favoritism is not morally wrong.

Deontology would also say that this world is morally broken, since promoting murder and suicide is not universalizable. However, because of overpopulation, it seems that not promoting these things in certain circumstances will ultimately violate Utilitarianism and Deontology, since the rational human beings worthy of life will all be wiped out.

The Garden is not a utopia. But despite its imperfections, it is hard to say that it is worse than the world we live in. We already have systems that tear families apart, unjustified murders happen daily, and we still experience war, genocide, disease, and death. The world presented in the story gives people autonomy and takes away many of these issues, which suggests that it is far better than the one we live in. The world is presented as the best we could do, no matter how morally ambiguous it might be. For that reason, the Garden is not a utopia, but it might provide a kind of goal to work towards.